The squat is considered one of the best (if not the best) exercise for increasing strength and stability of the muscles of the lower extremity – due to it’s activation of the large musculature of the hip and knee, as well as abdominals and erector spinae. It’s ability to improve power and strength has made it a staple in almost any strength and conditioning program, across virtually all sports. As a result, it’s important to understand the biomechanical differences between the Front Squat and Back Squat, to optimise results and reduce the risk of injury; while also allowing athletes to train around pain

TORSO POSITION

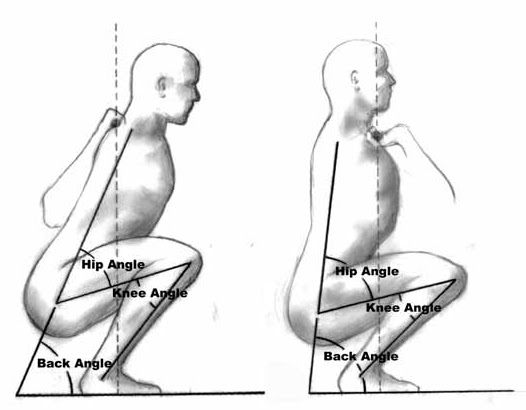

The most obvious difference between the two is trunk position. A proper front squat requires a more upright position than the back squat. Furthermore, the bar position anterior to the Lumbar Spine forces a higher engagement of the abdominals to stabilize the spine.

CENTRE OF MASS POSITION – HIP FLEXION vs KNEE FLEXION

The change in position of the centre of mass of the bar between the Front Squat and Back Squat means significant differences in terms of muscle recruitment. The Front Squat places more emphasis on the Quadriceps due to larger angles of Knee Flexion; whereas the Back Squat has larger angles of Hip Flexion, resulting in higher engagement of the posterior chain (Glutes, Hamstrings, Erector Spinae)

LUMBAR SPINE

Lower back injury risk is higher in the Back Squat, due to a more forward trunk lean, leading to greater demands from the trunk extensor, and higher lumbar shear forces. A more upright trunk (Front Squat) has a decreased in compressive forces and Lumbar spine shear forces, and as a result, a lower risk of injury to the lower back.

WEIGHT LIFTED

Due to higher involvement of the larger joints during a back squat (hip vs knee dominant), individuals are likely to be able to life more weight with the Back Squat vs Front Squat. However, a study by Gullett et al (2009) demonstrated that although more weight can be lifted during the back squat, muscle activity tested equally at 75% of 1RM – therefore, the same workout can be achieved with less weight on a front squat, and with less strain on the lumbar region – making it a staple for individuals with low back pain

KNEE PAIN

It’s not all sunshine and rainbows for the case for the Front Squat vs Back Squat. Due to the higher degrees of knee flexion in the front squat, there is a higher compressive force on the knee (Patellofemoral and Tibiofemoral)– which must be absorbed by the Meniscus and hyaline cartilage of the knee. Therefore, individuals with meniscal damage or Osteoarthritis, or Patellofemoral pain would benefit more from the back squat because it involves less knee flexion

ANKLE AND THORACIC MOBILITY

Due to the upright torso and higher knee flexion angles, the front squat requires more ankle dorsiflexion and thoracic extension to allow proper execution. Lack of these can result in a host of technique faults, including – butt-wink, dynamic knee valgus, pronation of the mid-foot and rounding of the Lumbar spine. Therefore, individuals should be screened for adequate thoracic extension and ankle dorsiflexion before attempting a loaded front squat

TRAINING AROUND PAIN

Individuals with knee pain (Tibiofemoral – meniscus injuries, OA; Patellofemoral) will be less symptomatic with back squats – due to less knee flexion. Individuals with low back pain will benefit from Front squats due to less shear and compressive forces on the Lumbar spine.

| FRONT SQUAT | BACK SQUATS | |

| MOBILITY DEMANDS | ||

| Thoracic Extension | Higher | Lower |

| Knee Flexion | Higher | Lower |

| Ankle Dorsiflexion | Higher | Lower |

| Wrist Extension | Higher | Lower |

| Hip Flexion | Lower | Higher |

| Hip Rotation | Lower | Higher |

| Shoulder (GH) Rotation | Lower | Higher |

| COMPRESSIVE FORCE | ||

| Knee | Higher | Lower |

| Lumbar Spine | Lower | Higher |

| SHEAR STRESS | ||

| (Depends on depth) | Knee | Lumbar Spine |

SOURCES

McKean, M. R., Dunn, P. K., & J Burkett, B. (2010). The lumbar and sacrum movement pattern during the back squat exercise. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 24, 2731.

Gullett, J. C., Tillman, M. D., Gutierrez, G. M., & Chow, J. W. (2009). A biomechanical comparison of back and front squats in healthy trained individuals. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 23, 284.

Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). Squatting kinematics and kinetics and their application to exercise performance. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 24, 3497.